|

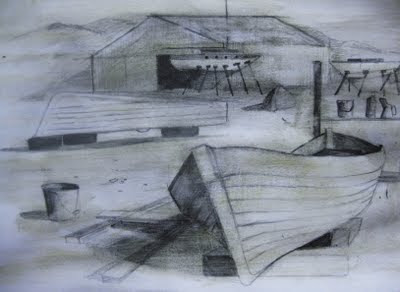

| drawing by Paul Kennedy |

Much has been written over the years about the McGruer dynasty,

narrating how they got started, building small boats at Glasgow Green

before moving down river, and the subsequent exploits and achievements

of this most talented and inventive family. I thought it would be

interesting to put together some notes about the methods which they used

and the workers involved. Over the years I have met many former

employees, indeed it was suggested by a friend who lived in Helensburgh

that formerly most of the local craftsmen were trained at McGruers.

It

was a tragedy that latterly there were no younger people coming forward

to be trained, or possibly the company was not offering

apprenticeships, just when there was a world-wide resurgence of interest

in wooden yachts. When the original company finally went into

liquidation at the end of 2001, having not built any new wooden boats

for about ten years, they were the last of the famous Scottish yards to

shut down. (That company is not to be confused with a new company of the

same name, which carries on surveying and other services.)

When

the McGruers moved from Tighnabruaich to Hattonburn at Clynder in 1914

to establish themselves for the first time in their own yard an

attraction was said to be the burn with its running water, which gave

the power for a mill to generate electricity. Whether or not this is so,

by the time the Islanders were built the yard was served by a steam

donkey engine driving a wide range of electric tools. Early on the

family had realised the benefits of electric power. They had purchased

not only powered saws, but more specialised devices such as electric

screwdrivers. Some of these came from abroad, France being one place

where there were specialist manufacturers. Some were invented and made

locally by engineers working in the various industries in the Glasgow

area.

Having

access to powered hand tools slung from overhead cables must have made

the work less arduous and uncomfortable. One of the most useful tools

was a spindle cutter set in a workbench, on which planks could be cut

out conform to a pattern. This was operational when the yard started to

build Dragons about 1926. They would cut complete sets of planks for a

Dragon, three copies of each plank, so that they were always left with

patterns for the next boat. The hulls were of course planked up on

standard moulds, so truly what was going on was an early version of

mass production. The safety aspects of such installations before such

things were fully understood would be an interesting subject for further

research.

The

family did appreciate the dangers of making large lead castings and

only the smallest keels were made on site. Normally a pattern would

simply be sent to one of the numerous shipyards in Glasgow, Port Glasgow

or Greenock. Latterly Morris & Lorimers were casting most of the

keels. There was a master pattern for each type of keel, Dragon,

Scottish Islander or whatever.

There

were also plenty of local blacksmiths and engineers to turn out the

required metalwork. When the Islands Class boats were built the practice

was to use iron bolts, even thought these were incompatible with lead

keels. Probably this was because the local blacksmiths could not work

with bronze, which is usually turned rather than forged. When

eventually the company started to use aluminium bronze, which is easier

to work, they made their own. McGruers did operate various steamboxes,

latterly using a twenty foot long tube with a double boiler.

Although

innovative, McGruers did not try building boats upside down, which is

much easier than right way up. Indeed this seems to have been pioneered

by American rather than European builders. Shadow moulds would be set up

in traditional fashion, the hulls planked up, then the stringers and

any steamed frames put in.

When

the order was received for the first five Islanders in the winter of

1928 the possibilities for mass production were fully exploited. The

hulls were quickly assembled from standard moulds and patterns and the

boats then finished side by side. They were all ready for their new

owners to select their boats by lot in time for the 1929 season.

At

just over twentyeight feet Islanders were the largest boats that could

be built from continuous planks without joints. The hull shape is so

easy that no steaming was needed. Conform to the traditional Scottish

(and Scandinavian) practice there was no garboard. The planks were

allowed to taper forward to a feather edge as they met the wooden keel.

There was no fuss, stress or complicated joinery work such as is needed

with boats built to the Anglo-American tradition with a wide garboard

strake. The topsides were planked first, the planks slightly wider

forward to meet the stem nicely, then the bottom was planked up simply

as one would build a brick wall. The only disadvantage of this method

that I am aware of is that the feather edge can be easily damaged when

the plank has to be removed to allow subsequent repairs. The method

lends itself, of course, to the use of narrow planks such are harvested

in the North of Europe.

A

variety of timber was used in building the Islanders. The keel, stem

and stern -post were of oak, the horn timber of teak, the hull planking

of pitch-pine and the timbers American rock elm. The transom,

cabin-sides and furniture were of mahogany, the decks planked with

tongue-and-groove yellow pine. The large components would be difficult

to build today in the same materials. For example the transom has a

radius of almost three inches and would have been chopped from a massive

slab over four feet long by eighteen inches deep. It is interesting to

note that Isla, built thirty years after the first boats, has a flat

transom, which would have been much more economical.

Old-growth

pitch pine was imported from Canada up to 1939, when supplies stopped

for the War and did not resume thereafter. It is excellent for hull

planking, there being several examples of boats still afloat after well

over one hundred years. Enormous teak and mahogany logs, up to four feet

square, would arrive by sea and would be rendered into workable boards

at Gilmour & Aitken's yard in Jamestown, Alexandria. They still

supply excellent timber.

The

hulls were fastened up with a mixture of metals, suggesting that the

yard had little understanding, or more likely little concern about the

effects of this in salt water, and of course the boats had no electrics.

The major components were held together with iron drifts, the bolts in

the lead keel were also iron, while the hull planking was secured with

copper nails, bent over rather than rooved. This practice is again

consistent with the Scottish and Scandinavian rather than Anglo-American

tradition. It leaves the timbers cleaner and neater, is easy to do as

well as lighter and cheaper. The deck planking was held on with iron

nails driven into deck-beams which were not dove-tailed, but simply

nailed into notches in the shelf. The chain-plates were simply bolted

through the shelf, unbelievable given that the boats were to be raced

hard.

Comparing

the boats as built with Alfred Mylne's plans shows a number of

variations. For example the front corners of the cabin were drawn

curved, but were built square. Alfred Mylne and the McGruers worked

together constantly, indeed at the time the yard mainly built to his

designs, so one can assume he approved of what they did. The Islands

Class plans were cleverly drawn for cheap construction and perhaps

Alfred Mylne was having a little joke with the corners.

Certainly

it was touch and go with the Class getting built at all, because

McGruers had said they needed seven orders to hold their price and they

only got five. By using what metals could be got and doing without

dove-tails etcetera they were trying to preserve some profit.

By

contrast with the other metal- work, which was made locally and was

somewhat agricultural the rudderhead fittings were skilfully cast and

fabricated from bronze. It would be interesting to know how and by whom

this was done.

Around

the time the boats were built the workforce would have numbered about

thirty permanent workers, local residents and usually the family of

older employees. In Spring local painters and labourers would swell the

ranks to deal with fitting out the fleet of racing and cruising boats

that wintered at the yard. Many of these were paid hands on the yachts.

Most

of the tools used in boatbuilding are special and the workforce had to

make their own, many of which of course passed down within families.

These included shaped planes with wooden soles and various jigs and

gadgets.

Although

conditions must have been hard, working through the winter in sheds

only partly protected from the weather, the workforce is reputed to have

been extremely happy. I was told by a long-retired boatbuilder that

when a boat was reaching an interesting stage everyone would be

desperate to get in to work in the morning. Of course at the same time

ship-building in the Clyde yards was going on entirely in the open, so

perhaps McGruer's men felt themselves lucky. Both types of activity

involved exciting creative work which sometimes had to substitute for

proper pay. McGruers' workforce could also reflect that they worked for

one of the best-known yards and even in bad times there would be a

reasonable order-book and job security for the permanent employees at

least. At one of the smaller yards in the area it was not uncommon for

there to be no wages at the end of the week and the local publican had

to offer an informal banking service.

Update: After this post appeared at first my attention was drawn to the fact that the Classic Boat articles about the yard had been posted and can be read online at http://clyde19-24.org.uk/

Update: After this post appeared at first my attention was drawn to the fact that the Classic Boat articles about the yard had been posted and can be read online at http://clyde19-24.org.uk/

What an excellent read, I used to live in Cylinder in the early 80's from the age of 7 to 11 and always remember sneaking through the building with my neighbour pal looking at part finished boats! I can still recall the smell of burnt wood and the dust then getting chased by the watchman or someone like that ( didn't hang about to find out!!)

ReplyDeleteI will driving by that area next week after40 years to see the changes

Excellent read, as a wee boy 40 odd years ago I lived in Clynder where me an my neighbour pal would go on adventures! And I always remember sneaking through the boat builders there to which the smell of burnt wood and sawdust is still imprinted in my sensory brain- then being chased by the watchman or someone who worked there, sacred to death then but now I always laugh at it, not doing damage but just curious.... brilliant time of life,

ReplyDeleteI'm returning there next week after40 years to see my old childhood home and the changes that have been made

Yes, a good read, I served my time in McGruers, it began in 1969 and they were the best years of my life. Working with the best tradesmen (and not forgetting Liz!!) The McGruer family were great people to know. I started in the drawing office learning the trade from conception, right through the build process to the launch. Involved in the construction of the most beautiful boats including, Cullaun of Kinsale to the new workboat "Jenny"

ReplyDeleteGreat times and better memories!