|

| Peking, image courtesy of www.laeisz.de |

The story of Ferdinand Laeisz contains lessons for anyone wanting to arrive safely and quickly under sail. That so many of the "Flying P" ships survived into the Twentieth Century to become sail training ships and later museum ships is testament to that.

In the final years of the sailing fleet, when merchant seamen were regarded as expendable and most sailing ships were operated on shoe string budgets as bulk carriers, Herr Laeisz continued to build ships that attracted premium cargos. With the best sails and rigging used in the hardest weather the ships could stand on in virtually all conditions. Captains were retired at forty five and sent to Head Office, while still fresh and competent. Steam tugs based in Hamburg would tow the outgoing ship until clear of the English Channel, then wait there for the next incomer. Compare the appalling losses inflicted on Scottish ships, such as the lovely Firth of Cromarty, blown ashore at St Margarets Bay near Dover on Burns Night 1894 and later wrecked at Corsewall Point in August 1898 by a South Westerly gale.

Herr Laiesz was aware of the problems inherent in policies of marine insurance. A ship could run aground in some part of the world, say South America, remote from the underwriters and have to wait months while communications passed before repairs could be done. His company carried its own insurance, with the Captain equipped with a power of attorney enabling him to pledge the company's credit and commission repairs locally.

Marine insurance is effectively a wager between three parties, shipowner, charterer and freight-owner on one hand and the underwriter on the other with agreed values that the latter will pay out without argument after total loss. It must have been exciting in the early days of the Trans-Atlantic trade when profit from the first voyage paid for the ship, the second the cargo and thereafter pure profit. One can imagine the tough Eighteenth century Glasgow tobacco lords parading the old Tontine hotel and striking bargains.

The hangover of this today is a serious problem for anyone owning a classic sailing yacht, in contrast to a production fibreglass vessel.

If one's floating plastic retreat were to be lost, probably in a marina, as such things rarely venture out to sea, the insurers would simply pay out sufficient to replace her with another, based on the abundance of sales evidence. One's ancient classic, built by one of our legendary yards a hundred years ago, might have been dug out of a mud berth and bought for £1, restored to perfection without counting the cost and now worth simply what someone is willing to pay in a very limited and specialised market place. In the absence of evidence of value will the sum insured come anywhere near the likely cost of repair? Presumably the insurer will apply the average clause and only pay out a fraction.

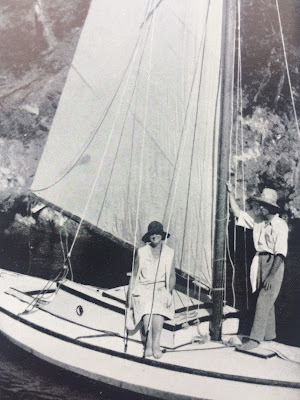

|

| Yacht Kentra, in need of some minor repairs! |

With some classes of yacht, the Garelochs for example, you are not allowed to build a new ship. There is an old story of an owner arriving at Clynder in the old days with a broken hatch cover and asking Mr McGruer to "repair my boat". One has to assume that he didn't expect his insurers to pay for this.

|

| Juno |

|

| Limpie |

|

| Galatea |

Perhaps the answer is to insure out boats third party only and put aside a sum each year towards potential repairs, taking a hint from Ferdinand Laeisz.

No comments:

Post a Comment